People:Malcolm X

Malcolm X

| |

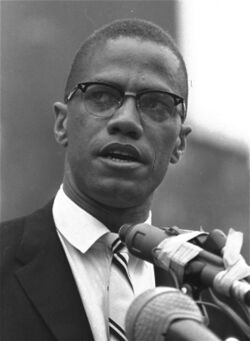

| Caption | Malcolm X giving a speech. |

|---|---|

| Birth Date | 1925-5-19 |

| Birth Place | Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Death Date | 1965-2-21 |

| Death Place | New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Minister, Activist |

| Industry | |

| Organizations | Nation of Islam,Muslim Mosque, Inc.,Organization of Afro-American Unity |

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an African American revolutionary, Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement until his assassination in 1965. A spokesman for the Nation of Islam (NOI) until 1964, he was a vocal advocate for Black empowerment and the promotion of Islam within the African American community. A controversial figure accused of preaching violence, Malcolm X is also a widely celebrated figure within African American and Muslim communities for his pursuit of racial justice.

Malcolm spent his adolescence living in a series of foster homes or with relatives after his father's death and his mother's hospitalization. He committed various crimes, being sentenced to 8 to 10 years in prison in 1946 for larceny and burglary. In prison, he joined the Nation of Islam, adopting the name MalcolmTemplate:NbspX to symbolize his unknown African ancestral surname while discarding "the white slavemaster name of 'Little'", and after his parole in 1952, he quickly became one of the organization's most influential leaders. He was the public face of the organization for 12 years, advocating Black empowerment and separation of Black and White Americans, and criticizing Martin Luther King Jr. and the mainstream civil rights movement for its emphasis on non-violence and racial integration. Malcolm X also expressed pride in some of the Nation's social welfare achievements, such as its free drug rehabilitation program. From the 1950s onward, Malcolm X was subjected to surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

In the 1960s, Malcolm X began to grow disillusioned with the Nation of Islam, as well as with its leader, Elijah Muhammad. He subsequently embraced Sunni Islam and the civil rights movement after completing the Hajj to Mecca and became known as "el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz," which roughly translates to "The Pilgrim Malcolm the Patriarch". After a brief period of travel across Africa, he publicly renounced the Nation of Islam and founded the Islamic Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI) and the Pan-African Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). Throughout 1964, his conflict with the Nation of Islam intensified, and he was repeatedly sent death threats. On FebruaryTemplate:Nbsp21, 1965, he was assassinated in New York City. Three Nation members were charged with the murder and given indeterminate life sentences. In 2021, two of the convictions were vacated. Speculation about the assassination and whether it was conceived or aided by leading or additional members of the Nation, or with law enforcement agencies, has persisted for decades.

He was posthumously honored with Malcolm X Day, on which he is commemorated in various cities across the United States. Hundreds of streets and schools in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, while the Audubon Ballroom, the site of his assassination, was partly redeveloped in 2005 to accommodate the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center. A posthumous autobiography, on which he collaborated with Alex Haley, was published in 1965.

| |

| Caption | Malcolm X giving a speech. |

|---|---|

| Birth Date | 1925-5-19 |

| Birth Place | Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Death Date | 1965-2-21 |

| Death Place | New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Minister, Activist |

| Industry | |

| Organizations | Nation of Islam,Muslim Mosque, Inc.,Organization of Afro-American Unity |

Early years

Malcolm Little was born May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, the fourth of seven children of Grenada-born Louise Helen Little (née Langdon) and Georgia-born Earl Little.[1] Earl was an outspoken Baptist lay speaker, and he and Louise were admirers of Pan-African activist Marcus Garvey. Earl was a local leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and Louise served as secretary and "branch reporter", sending news of local UNIA activities to Negro World; they inculcated self-reliance and black pride in their children.[2][3][4] MalcolmTemplate:NbspX later said that White violence killed four of his father's brothers.[5]

Because of Ku Klux Klan threats, Earl's UNIA activities were said to be "spreading trouble"[6] and the family relocated in 1926 to Milwaukee, and shortly thereafter to Lansing, Michigan.[7] There, the family was frequently harassed by the Black Legion, a White racist group Earl accused of burning their family home in 1929.[8]

When Malcolm was six, his father died in what has been officially ruled a streetcar accident, though his mother Louise believed Earl had been murdered by the Black Legion. Rumors that White racists were responsible for his father's death were widely circulated and were very disturbing to Malcolm X as a child. As an adult, he expressed conflicting beliefs on the question.[9] After a dispute with creditors, Louise received a life insurance benefit (nominally $1,000 Template:Mdashbabout $Template:Inflation,000 in 2023)Template:Inflation-fn in payments of $18 per month;[10] the issuer of another, larger policy refused to pay, claiming her husband Earl had committed suicide.[11] To make ends meet, Louise rented out part of her garden, and her sons hunted game.[10]

During the 1930s, white Seventh-day Adventists witnessed to the Little family; later on, Louise Little and her son Wilfred were baptized into the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Malcolm said the Adventists were "the friendliest white people I had ever seen."[12]

In 1937, a man Louise had been datingTemplate:Mdashbmarriage had seemed a possibilityTemplate:Mdashbvanished from her life when she became pregnant with his child.[13] In late 1938, she had a nervous breakdown and was committed to Kalamazoo State Hospital. The children were separated and sent to foster homes. Malcolm and his siblings secured her release 24 years later.[14][15]

Malcolm attended West Junior High School in Lansing and then Mason High School in Mason, Michigan, but left high school in 1941, before graduating.[16] He excelled in junior high school but dropped out of high school after a White teacher told him that practicing law, his aspiration at the time, was "no realistic goal for a nigger."[17] Later, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX recalled feeling that the White world offered no place for a career-oriented Black man, regardless of talent.[17]

From age 14 to 21, Malcolm held a variety of jobs while living with his half-sister Ella Little-Collins in Roxbury, a largely African American neighborhood of Boston.[19][20]

After a short time in Flint, Michigan, he moved to New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1943, where he found employment on the New Haven Railroad and engaged in drug dealing, gambling, racketeering, robbery, and pimping.[21] According to biographer Bruce Perry, Malcolm also occasionally had sex with other men, usually for money, though this conjecture has been disputed by those who knew him.[22][23]Template:Efn-ua He befriended John Elroy Sanford, a fellow dishwasher at Jimmy's Chicken Shack in Harlem who aspired to be a professional comedian. Both men had reddish hair, so Sanford was called "Chicago Red" after his hometown, and Malcolm was known as "Detroit Red". Years later, Sanford became famous as comedian and actor Redd Foxx.[24]

Summoned by the local draft board for military service in World WarTemplate:NbspII, he feigned mental disturbance by rambling and declaring: "I want to be sent down South. Organize them nigger soldiersTemplate:Nbsp... steal us some guns, and kill us [some] crackers".[25][26][27] He was declared "mentally disqualified for military service".[25][26][27]

In late 1945, Malcolm returned to Boston, where he and four accomplices committed a series of burglaries targeting wealthy White families.[28] In 1946, he was arrested while picking up a stolen watch he had left at a shop for repairs,[29] and in February began serving a sentence of eight to ten years at Charlestown State Prison for larceny and breaking and entering.[30] Two years later, Malcolm was transferred to Norfolk Prison Colony (also in Massachusetts).[31][32]

Nation of Islam period

Prison

When Malcolm was in prison, he met fellow convict John Bembry,[33] a self-educated man he would later describe as "the first man I had ever seen command total respectTemplate:Nbsp... with words".[34] Under Bembry's influence, Malcolm developed a voracious appetite for reading.[35]

At this time, several of his siblings wrote to him about the Nation of Islam, a relatively new religious movement preaching Black self-reliance and, ultimately, the return of the African diaspora to Africa, where they would be free from White American and European domination.[36] He showed scant interest at first, but after his brother Reginald wrote in 1948, "Malcolm, don't eat any more pork and don't smoke any more cigarettes. I'll show you how to get out of prison",[37] he almost instantly quit smoking and began to refuse pork.[38]

Following a visit during which Reginald detailed the group's teachings, including the notion that White people are considered devils, Malcolm initially struggled to accept this belief. Over time, however, Malcolm reflected on his past relationships with White individuals and concluded that they had all been marked by dishonesty, injustice, greed, and hatred.[39] Malcolm, whose hostility to Christianity had earned him the prison nickname "Satan,"[40] became receptive to the message of the Nation of Islam.[41]

In late 1948, Malcolm wrote to Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad advised him to renounce his past, humbly bow in prayer to God and promise never to engage in destructive behavior again.[42] Though he later recalled the inner struggle he had before bending his knees to pray,[43] Malcolm soon became a member of the Nation of Islam,[42] maintaining a regular correspondence with Muhammad.[44]

In 1950, the FBI opened a file on Malcolm after he wrote a letter from prison to President Harry S. Truman expressing opposition to the Korean War and declaring himself a communist.[45] That year, he also began signing his name "MalcolmTemplate:NbspX."[46] Muhammad instructed his followers to leave their family names behind when they joined the Nation of Islam and use "X" instead. When the time was right, after they had proven their sincerity, he said, he would reveal the Muslim's "original name."[47] In his autobiography, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX explained that the "X" symbolized the true African family name that he could never know. "For me, my 'X' replaced the white slavemaster name of 'Little' which some blue-eyed devil named Little had imposed upon my paternal forebears."[48]

Early ministry

After his parole in August 1952,[49] MalcolmTemplate:NbspX visited Elijah Muhammad in Chicago.[50] In June 1953, he was named assistant minister of the Nation's Temple Number One in Detroit.[51]Template:Efn-ua Later that year he established Boston's Temple NumberTemplate:Nbsp11;[52] in March 1954, he expanded Temple NumberTemplate:Nbsp12 in Philadelphia;[53] and two months later he was selected to lead [[Mosque No. 7|Temple NumberTemplate:Nbsp7]] in Harlem,[54] where he rapidly expanded its membership.[55]

In 1953, the FBI began surveillance of him, turning its attention from MalcolmTemplate:NbspX's possible communist associations to his rapid ascent in the Nation of Islam.[56]

During 1955, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX continued his successful recruitment of members on behalf of the Nation of Islam. He established temples in Springfield, Massachusetts (NumberTemplate:Nbsp13); Hartford, Connecticut (NumberTemplate:Nbsp14); and Atlanta (NumberTemplate:Nbsp15). Hundreds of African Americans were joining the Nation of Islam every month.[57]

Besides his skill as a speaker, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX had an impressive physical presence. He stood Template:Convert tall and weighed about Template:Convert.[58] One writer described him as "powerfully built",[59] and another as "mesmerizingly handsomeTemplate:Nbsp... and always spotlessly well-groomed".[58]

Marriage and family

In 1955, Betty Sanders met MalcolmTemplate:NbspX after one of his lectures, then again at a dinner party; soon she was regularly attending his lectures. In 1956, she joined the Nation of Islam, changing her name to BettyTemplate:NbspX.[60] One-on-one dates were contrary to the Nation's teachings, so the couple courted at social events with dozens or hundreds of others, and MalcolmTemplate:NbspX made a point of inviting her on the frequent group visits he led to New York City's museums and libraries.[61]

MalcolmTemplate:NbspX proposed during a telephone call from Detroit in January 1958, and they married two days later.[62][63] They had six daughters: Attallah (b. 1958; Arabic for "gift of God"; perhaps named after Attila the Hun);[64]Template:Efn-uaTemplate:Efn-ua Qubilah (b. 1960, named after Kublai Khan);[65] Ilyasah (b. 1962, named after Elijah Muhammad);[66] Gamilah Lumumba (b. 1964, named after Gamal Abdel Nasser and Patrice Lumumba);[67][68] and twins Malikah (1965–2021)[69] and Malaak (b. 1965, both born after their father's death, and named in his honor).[70]

Hinton Johnson incident

The American public first became aware of MalcolmTemplate:NbspX in 1957, after Hinton Johnson,Template:Efn-ua a Nation of Islam member, was beaten by two New York City police officers.[71][72] On AprilTemplate:Nbsp26, Johnson and two other passersbyTemplate:Mdashbalso Nation of Islam membersTemplate:Mdashbsaw the officers beating an African American man with nightsticks.[71] When they attempted to intervene, shouting, "You're not in AlabamaTemplate:Nbsp... this is New York!"[72] one of the officers turned on Johnson, beating him so severely that he suffered brain contusions and subdural hemorrhaging. All four African American men were arrested.[71]

Alerted by a witness, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX and a small group of Muslims went to the police station and demanded to see Johnson.[71] Police initially denied that any Muslims were being held, but when the crowd grew to about five hundred, they allowed MalcolmTemplate:NbspX to speak with Johnson.[73] Afterward, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX insisted on arranging for an ambulance to take Johnson to Harlem Hospital.[74]

Johnson's injuries were treated and by the time he was returned to the police station, some four thousand people had gathered outside.[73] Inside the station, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX and an attorney were making bail arrangements for two of the Muslims. Johnson was not bailed, and police said he could not go back to the hospital until his arraignment the following day.[74] Considering the situation to be at an impasse, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX stepped outside the station house and gave a hand signal to the crowd. Nation members silently left, after which time the rest of the crowd also dispersed.[74]

One police officer told the New York Amsterdam News: "No one man should have that much power."[74][75] Within a month the New York City Police Department arranged to keep MalcolmTemplate:NbspX under surveillance; it also made inquiries with authorities in other cities in which he had lived, and prisons in which he had served time.[76] A grand jury declined to indict the officers who beat Johnson. In October, MalcolmTemplate:NbspX sent an angry telegram to the police commissioner. Soon the police department assigned undercover officers to infiltrate the Nation of Islam.[77]

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Carson, p.Template:Nbsp108.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ MalcolmTemplate:NbspX, Autobiography, p.Template:Nbsp178; ellipsis in original.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Shabazz, Betty, "MalcolmTemplate:NbspX as a Husband and Father", Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.